Demolition by Neglect is ‘the destruction of a building through abandonment or lack of maintenance’.

Deliberate or intentional neglect is when an owner is deliberately not maintaining or securing a building, despite having the means to do so, with the aim of gaining a demolition permit.

Demolition by Neglect

Identifying the problem

In 2013 the National Trust commissioned a report on the issue of demolition by neglect in Victoria. In 2014, with the support of the Heritage Council of Victoria, we facilitated a forum of planners and experts to formulate policy initiatives to deal with the issue at local government level.

The turning point

In 2016, Carlton’s 1857 Corkman Irish Pub was illegally demolished by developers seeking a more profitable use of the land. This loss was felt profoundly by the local community, the pub having long served as a gathering place for a diverse array of people; students, residents, workers, politicians, and more.

Timeline of the Corkman Irish Pub - Case study

2016

If you want to get away with murder, it’s probably unwise to attempt it in the shadow of a law faculty. But that’s exactly what the owners of the former Corkman Irish Pub (Carlton Inn) did on a mid-October weekend in 2016, demolishing the historic 1857 pub identified by Melbourne City Council as “one of the earliest extant buildings in this part of Carlton”, opposite Australia’s oldest law school.

Law students from the University of Melbourne were quick to react, mounting a campaign to “Resurrect the Corkman”. An online petition that gathered over 5,000 signatures in less than 24 hours, with all major (and some minor) news outlets picking up the issue.

The most urgent issue to be addressed was that of unlawful demolition. The City of Melbourne confirmed that “neither a planning permit or building permit had been issued for the demolition of the building and there [were] no approved plans for its future development”.

Following the demolition, politicians across the political spectrum united in calls for the rogue developers to feel the full force of the law, which turned out to be rather unimpressive.

Soon after the demolition of the pub, the Minister for Planning and City of Melbourne jointly applied to VCAT for an enforcement order requiring the reconstruction of the pub. A similar application was also made by students from Melbourne Law School, which is opposite the Corkman Hotel site.

The enforcement proceedings essentially sought that the land be restored to its prior condition (i.e. that the building be reinstated on the land to the same condition and form, reusing materials from the demolished building where practical and safe to do so).

2017

The Minister for Planning gazetted Design and Development Overlay Schedule 68 (DDO68), which required restoration and reconstruction in facsimile of the building as it stood immediately prior to demolition. It was argued by the developers that the DDO amounted to a punitive measure for the illegal demolition, but that it is unlawful to use the Planning Scheme as a punitive instrument.

2018

In December 2018, the Minister for Planning gazetted Planning Scheme Amendment C346, which required that before any development is approved, the landowner must prepare an Incorporated Plan which includes the site context and surrounding development, a Heritage Response Plan and a plan showing the form of the proposed future development. The Incorporated Plan must demonstrate consideration of the historical, cultural and social significance of the site and the scale, design and materials of previous buildings on the site. However, this placed the onus on the developer to determine the heritage response. In addition, the planning scheme allowed for a 40m building on the site (approximately 12 storeys), under Design and Development Overlay 61.

At the same time, the Minister introduced Planning Scheme Amendment VC155, which applied to all planning schemes across the state, enabling decision-makers to consider whether it is appropriate to require the restoration or reconstruction of a heritage building in a Heritage Overlay that has been unlawfully or unintentionally demolished, to retain or interpret the cultural heritage significance of the building, streetscape or area.

2019

In May 2019, three years after the unlawful demolition of the Corkman Irish Pub, it was announced that an agreement had been reached between the developers, the State Government, and the City of Melbourne that could see a tower of up to 12-storeys built on the site, with no requirement to reconstruct the former pub.

The VCAT orders, which arose from an agreement by the parties reached in confidential mediation, required the site to be cleared and made into a temporary park until a permit was granted for a new development. A permit needed to be secured and development commenced by 30 June 2022, or the site owner would be required to rebuild the façade of the hotel. DDO68, which had required the restoration and reconstruction of a facsimile of the building as it stood prior to demolition, was repealed.

The National Trust was critical of this outcome and believed that further legislative reform to combat illegal demolition of heritage buildings was needed. Responding to the VCAT decision, then-CEO Simon Ambrose said, “If this is the best we can do under our current laws, we need to change them.”

Meanwhile, developers Raman Shaqiri and Stefce Kutlesovsk pleaded guilty to the Corkman’s illegal destruction at the Magistrates Court in January 2019. They were then fined almost $2m. However, in September, this fine was reduced to just over $1m after the pair appealed the penalty in the County Court. Judge Trevor Wraight, who delivered the sentence, acknowledged that this reduction may anger the community, however concluded that the offence did not warrant the maximum penalty according to current sentencing guidelines, stating:

It may be that the community – and possibly the sentencing Magistrates in this instance – regard the available maximum penalties in relation to this conduct as inadequate. However, unless and until Parliament increases the penalties available, Courts are bound by the proscribed penalty and must sentence in accordance with proper sentencing principle.

The sentencing decision included detailed accounts of the events which led up to and followed the unlawful demolition of the hotel, including enforcement action taken by the City of Melbourne, which was ignored by the developers who proceeded with the demolition after a Stop Work Order was issued.

Judge Wraight found that the actions of Shaqiri and Kutlesovski were a deliberate breach of law and motivated by the potential profit that could be gained from the demolition of the place, saying “the decision to demolish the Hotel was a deliberate, commercially informed decision which would have required a degree of pre-planning.” He also found that there was “little, if any, evidence of genuine remorse on behalf of Mr Saqiri and Mr Kutlesovski”.

The National Trust called on the State government to review penalties to reflect the significant value of heritage to the community and provide a strong deterrent to the destruction of heritage places. Noting that illegal demolition cannot just become part of the cost of doing business.

2020

On 28 October 2020, Sustainable Australia MP Clifford Hayes successfully introduced a motion in the Legislative Council calling for an Inquiry on the adequacy of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the Victorian planning framework in relation to planning and heritage protection.

The motion was supported by the Opposition and crossbenchers including Dr Samantha Ratnam, leader of the Victorian Greens. In his speech to the Chamber, Mr Hayes highlighted a number of heritage places lost to development in recent years.

Hayes also called out the inadequacy of penalties for the illegal demolition of heritage places, citing the developers of the Corkman Irish Pub, who had their fines cut on appeal, and were facing legal action for failing to deliver on state and local government requirements to turn the site into a public park pending permit approval for development.

2021

In late 2021 the former site of the Corkman was made into a publicly accessible park.

2022

In May 2022 the developers filed an application to amend their Enforcement Order, seeking further time to obtain a planning permit and begin the redevelopment of the site. Under the Enforcement Order requirements, “a planning permit [must be] obtained for the redevelopment of the land and substantial commencement of the development under the permit by 30 June 2022”. Otherwise, the developers would be required to rebuild external parts of the Corkman Hotel by 30 June 2023.

In October 2022 the developers lodged plans to Melbourne City Council proposing to build a three-storey hotel featuring an entertainment space they believed would provide opportunities for “social interaction and support a vital night-time economy providing music, food and entertainment”.

The National Trust saw the hotel proposal as an opportunity to continue the sites historical and social significance as a place of gathering and entertainment. However, we found it disappointing that no community consultation was undertaken to inform the plans, considering the huge impact the destruction of the Corkman Hotel had on the community.

2023

In July Melbourne City Council declared it would oppose the developer’s request to amend the Enforcement Order before VCAT in March 2024. “The applicant has not obtained a planning permit, has not commenced development and has not rebuilt the hotel – and therefore is in breach of the Enforcement Order,” a City of Melbourne spokesperson said.

2024

The former site of the Corkman Irish Pub remains as public open space pending the results of the VCAT hearing to amend the Enforcement Order and the developer’s application to successfully obtain a planning permit.

The state of legislation

The illegal demolition of the Corkman Irish Pub in Carlton was seen as a turning point for heritage protection in the state, with the ongoing saga of the site exposing the shortcomings of the 1987 Planning and Environment Act. Thus, in 2018 a state-wide review of the Heritage Act commenced, resulting in amendments being made in 2021 empowering local councils to enforce protection, deter demolition and stop developers from benefiting from illegal demolitions and demolition by neglect.

Through the following amendments under section 6B Councils can now:

- Regulate or prohibit the development of land on which there is or was a heritage building that has been unlawfully demolished, in whole or in part, or fallen into disrepair; and

- Require that a permit must not be granted for the development of land on which there is or was a heritage building that has been unlawfully demolished, in whole or in part, or fallen into disrepair, unless the development is for or includes the reconstruction or reinstatement of the building, in whole or in part; or the repair of the building.

In essence, any new development on a site following demolition by neglect of a heritage structure can be blocked by local government, ensuring benefit from development of the site would not be gained through demolition by neglect.

The amendments in action

Protective opportunities within the amendment have since been actioned by the City of Boroondara following the illegal demolition of Edwardian home Shenley Croft in Canterbury.

Shenley Croft - Case study

In late 2023, Victoria Police confirmed the fire that destroyed this locally significant heritage property was an arson attack. The matter is still undergoing investigation and no charges have been laid. Boroondara Council has also claimed the arson follows three years where the building was allowed to fall into disrepair and left vacant and inadequately secured since the property was transferred to new ownership.

In response to the confirmation of arson, Boroondara Council has enacted section 6B of the Planning and Environments Act by applying to the Minister for Planning to place a Special Controls Overlay (SCO) over the property, ensuring any further development on the site entails full reconstruction of the dwelling.

This utilisation of the new legislation ensures perpetrators will not economically benefit from the destruction of heritage and deters future acts of deliberate demolition by neglect.

The challenge of addressing neglect before it reaches demolition

The issue with legislation focused on demolition by neglect lies in its reactive nature, intervening only after the damage is done. While amendments to the Planning and Environment Act aim to dissuade intentional neglect, inadvertent negligence remains a concern. How can we pre-emptively tackle potential cases of neglect before they escalate to requiring demolition?

Local councils have taken proactive measures by implementing Local Laws addressing dilapidated and unsightly properties, empowering them to caution and penalize negligent property owners. A prime example is the City of Geelong’s utilisation of such laws to catalyse restoration at the long-neglected Ritz Hotel site.

Source: https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/11b2bd6b1ab630d9865692f97bda4f01

Ritz Hotel - Case study

The Ritz Hotel in Geelong represents a rich history of diverse uses, yet it languished vacant for decades, punctuated by repeated applications for demolition and redevelopment since 1984; the hallmarks of deliberate demolition by neglect.

Geelong’s 2014 introduction of a local amenity law aimed to curb neglect before it led to irreversible damage. By imposing fines on developers for each month that the neglect continued, the law incentivised restoration over continued neglect. Consequently, the Ritz Hotel’s facade was preserved, with the addition of a modern apartment complex constructed behind it. The National Trust, as a matter of principle, does not support facadism as an acceptable heritage practice.

Source: https://www.realestate.com.au/news/developers-turn-from-banks-to-secure-funds-for-geelongs-ritz-project/

Local Laws addressing dilapidated and unsightly properties have since been adopted by numerous municipalities. The legislation shows promise in addressing the onset of demolition by neglect, even unintentional instances, through proactive warnings and education, or even fines in compelling cases. While not exclusively tailored to heritage protection, the legislation’s triggers and enforcement mechanisms serve as a functional protective channel.

Nevertheless, implementing such measures poses challenges, requiring dedicated enforcement officers and a clear framework for identifying neglect. Given the nuanced nature of neglect, initial steps may involve issuing warnings and disseminating educational materials to property owners. Additionally, such local laws are not consistent across Councils, and many municipalities do not have the power to enforce maintenance of buildings beyond risks to public safety.

Controls at the State level

State listed properties are protected against demolition by neglect under the Heritage Act of 2017. Sections 87-89 of the Heritage Act enables Heritage Victoria to punish parties who ‘knowingly or recklessly [or negligently] remove, relocate or demolish, damage or despoil, develop or alter, or excavate, all or any part of a registered place.’

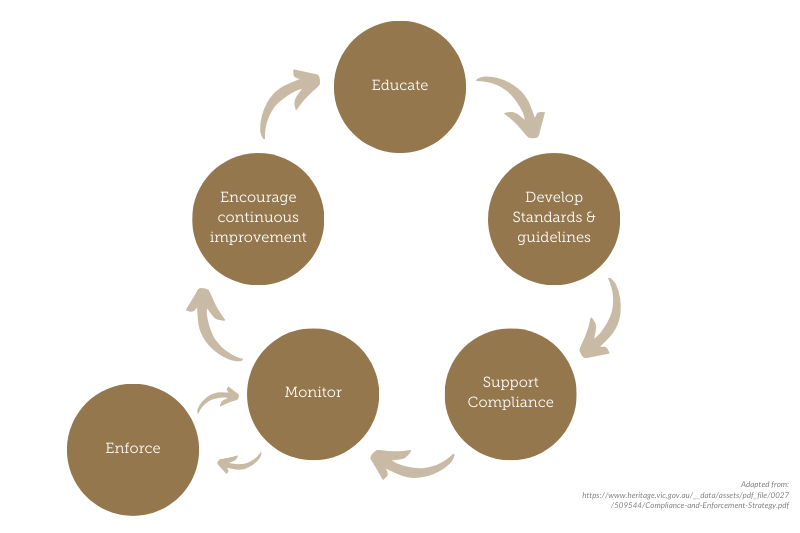

Heritage Victoria is active in enforcing good management of heritage properties to circumvent issues of demolition by neglect. The Compliance and Enforcement Strategy, introduced a graduated approach to enforcement, seeking to address each property equitably and reasonably.

The Heritage Victoria website features examples of recent instances where intervention has occurred to enforce protection of state listed heritage, a notable case is the Hoffman Brickworks site in Brunswick.

Hoffman Brickworks - Case study

A state-listed heritage site, the Former Hoffman Brickworks is one of the most historically important brickmaking sites in Australia, and is integral to the history of Brunswick’s economic and social development. The Hoffman company pioneered the industrialisation of brickmaking in Australia by introducing the revolutionary Hoffman kiln, for which the company had patent rights. The kilns were built to service the 1880’s ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ building boom, producing forty million bricks per year.

The Hoffman Brickworks has been plagued by decades of neglect leading to the loss of the 19th century Brick Pressing Shed and Steam Engine House. Developers ensured that the site was neglected, rendering the buildings unsafe, and leaving Heritage Victoria with no option but to approve the proposed developments in 2022. The Pressing Shed and the Engine House were specifically identified in the Victorian Heritage Register Statement of Significance as having primary and contributory heritage significance to the site.

In June 2023, developers of the Hoffman Bricks site were issued a Repair Order for the remaining heritage structures, signalling a shift towards enforcing preventive measures to avert further loss.

Recent amendments to enforcement legislation, under sections 152-168 of the Heritage Act 2017, Disrepair of registered place or registered object, hope to provide Heritage Victoria with the toolkit to prevent similar occurrences as the Hoffman Brickworks demolition from continuing.

What can you do to help?

Heritage belongs to all of us. It is important that we, as community custodians, know what to do when we see a heritage place falling victim to demolition by neglect and feel empowered to act. For concerns of locally protected heritage, contacting your local council is the best and most direct way to alert of illegal demolitions or neglect. For State listed heritage, Heritage Victoria accepts reports of unauthorised works on state heritage through its website. This infographic provided by the Heritage Council of Victoria is a great starting place for understanding the structure of heritage authorities.

Additionally, you can contact the National Trust Conservation & Advocacy team, we are the state’s premier community-based heritage advocacy organisation, working to actively protect and conserve places of heritage significance for future generations to enjoy. Our advocacy toolkit is a great resource to aid in supporting protection of heritage places.