Garden historian and National Trust horticultural adviser Merilyn Kuchel explores the unexpected history of a pioneering venture that produced olive oils of such quality they even wowed the French, winning a silver medal at the 1878 Paris Exhibition.

When Samuel Davenport was just a youth he dived into an ice-cold stream to save a man from drowning. He succeeded but for years after suffered from impaired lung function so his family sent him to the south of France, where he recuperated in a region famous for cultivating vines, olives and almonds. This experience proved invaluable when he emigrated to South Australia in 1843 with his new wife Margaret (nee Cleland) and older brother Robert to take up land at Macclesfield.

Samuel Davenport was a dutiful son and corresponded regularly with his father detailing their life and work. ‘You know, in the hills as much as the plains, I find this climate very similar to that of the French coast of [the] Mediterranean, therefore I say why should not their farming somewhat suit us,’ he wrote soon after arriving. Pointing out that the ‘olive is a staple commodity and source of great wealth. Its trees are hardy, very long lived…; the oil and fruit most saleable,’ he requested a large order be sent to him by the following year. ‘Packed in charcoal-dust the seed and the truncheons would keep good, I little doubt. Say 10,000 or 20,000 olives at least.’

In 1846, Governor Robe invited Davenport to take a seat on the Legislative Council. So he was closer at hand to carry out his duties, Samuel purchased Gleeville Farm for £700. Renaming it Beaumont, he subdivided and leased much of the acreage to pay off his debts and started planting olives along the boundaries. Two allotments were allocated to The Right Reverend Augustus Short, the first Anglican bishop of Adelaide, who built Beaumont House. When he could spare time, the bishop spent it in the garden, planting olives, figs, almonds and other trees given to him by Davenport. Samuel and Margaret took up residence in 1857, after Short moved to North Adelaide.

Davenport’s first experiments in crushing olives were in 1864, producing about one gallon of good oil. In 1866 he crushed 700 kilograms of ripe olives. Encouraged by the quality, he employed Margaret’s nephews George Fullarton Cleland and Tom Glen to build a factory on Dashwood Road and imported a Chilean mill. It crushed almost four tonnes of olives in 1874, including fruit purchased from neighbours and olives picked from Davenport’s own trees by children who were paid fivepence per two-gallon bucket.

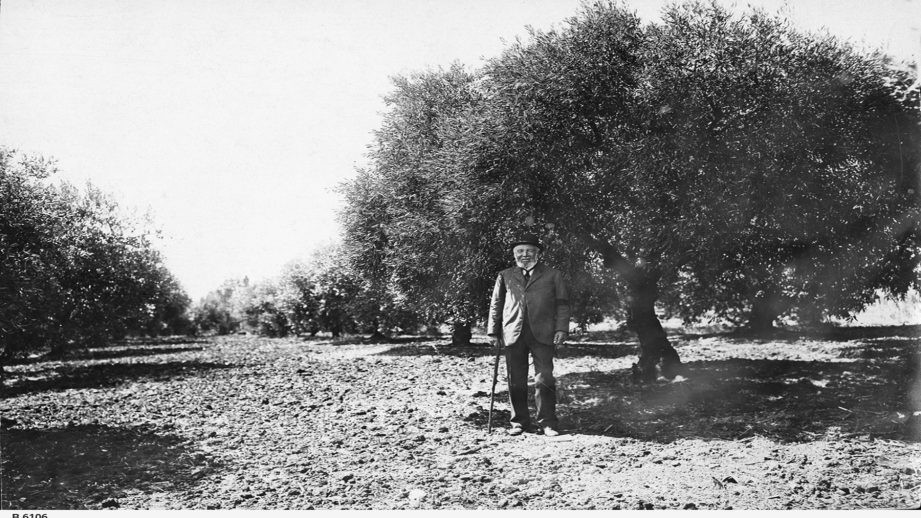

Cleland bought the factory in 1880, but named the virgin olive oil he produced after Davenport, continuing to build its reputation for quality and winning many awards. There was another major planting in 1883, from truncheons imported from Spain. By 1904, the business was processing about two thirds of the State’s annual production of around 20,000 gallons, using its own and purchased fruit. After Samuel’s death in 1906, G.F. Cleland and Sons continued to produce wine and award-winning oil. Meanwhile, Beaumont House passed through several owners.

When Kenneth Brock married Lilian Bennett (then the owner of Beaumont House) in 1938, the property consisted of 29 acres on which grew about 1400 olive trees covering 27 varieties. After his return from the Second World War, Kenneth set about revitalizing the old trees and began an olive tree nursery, which soon had customers all over Australia. The property was subdivided in the 1950s, and Lilian gave Beaumont House to the National Trust in 1967.

When the National Trust moved their headquarters to Beaumont in 2009, then President Anita Aspinall invited me to join a new garden committee and produce a management plan to guide renovation and maintenance. Expert advice was sought on the olive trees because of serious concerns about their declining health, elongated and brittle growth, and very small crops caused by overcrowding, lack of light and no pruning since the closure of the factory sometime in the 1960s. Among those consulted were leading horticulturalist Ian Tolley, Mark Lloyd from Coriole vineyards, arborists from the City of Burnside and Michael Johnston, then president of the Olive Association of SA. They all recommended radical pruning to encourage healthy new growth and increased fruit production.

Much to the consternation of many Burnside residents, radical pruning of the olives began in 2016 and continued over the next five years until all the trees in the grove had been rejuvenated. Since 2017 horticulture students from Urrbrae TAFE have assisted with the pruning, which has been a great help to the regular garden volunteers who work at Beaumont every Wednesday morning. In May 2017 volunteers under the guidance of Michael Johnston picked 330 kilograms of olives, which were crushed, free of charge, into 40 litres of oil by Domenic Scarfo from Diana Olive Oil at Willunga. The 2024 harvest in May yielded 76 litres. It will be available for sale at the Olive Festival on 11 April 2025