A rare collection of letters found in a suitcase at Woodford Academy tells the real-life story of Victorian lovers.

From 1887 to 1892, Henrietta Nielson and her future husband John McManamey wrote over 100 love letters to each other in the lead up to their marriage.

Stored in a small leather suitcase at Woodford Academy in the Blue Mountains on the lands of the Dharug people, the letters have survived intact for over a century and provide a rare insight into romantic correspondence of the 19th century.

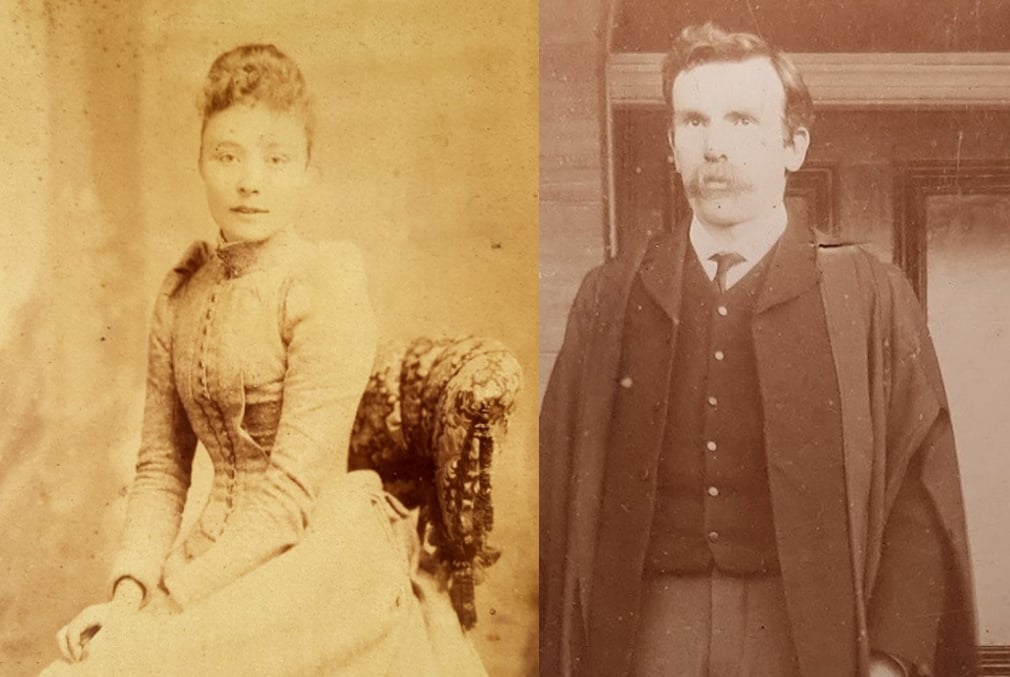

Henrietta was born in Bathurst in 1870 and worked as a governess and music teacher at rural properties in Central New South Wales. She was just 17 when Jack McManamey noticed how she ‘used to blush now & then as I began to find my way to the school at Forbes.’

Born in 1864, Jack was a classics scholar who had rebelled against his father’s wishes to study Law. After meeting Henrietta – affectionately known as Ettie – Jack sent his first awkward letter in February 1889, asking for her permission to initiate a ‘correspondence in which I hope you may be kind enough to share.’

Ettie and Jack’s correspondence spanned three years, right up to their marriage on 28 December 1892. In them, we see the universal passion and misunderstandings of young love. Often they hid phrases of love on the inside of envelopes, away from prying eyes. Jack even monitored the frequency and appearance of Ettie’s kisses:

Your last letter was very nice darling, but you forgot the kisses. But you will let me have twice as many from your lips themselves to supply the omission, will you not, my queen? …I shall only write two or three pages today, because you forgot to send me kisses in your last letter and in the preceding one.

As with all young love, trouble struck a year into their correspondence, when Ettie misunderstood Jack’s revelation that his father wasn’t happy about their engagement. Jack was the more poetic of the pair, but this cutting reply shows Ettie to be sensible and to the point. She wrote:

Dear Jack,

Would you kindly say in your next letter a little more clearly what you wish?

I am at present at a loss as to your meaning. In fact, the conclusion I have arrived at is that you want to break off the engagement, you cannot afford to marry, and wish to make a position at the Bar. I suppose you have discovered that we are not suited for each other and, if so, I suppose you are quite right in breaking it off at once. However I have no wish to be an obstacle in the way of your success and I suppose your father will not object to seeing if you do stay in Forbes. We shall not see each other except, I suppose, to return letters, etc.

Fortunately the two continued corresponding, and each hand-written letter reveals the ever-growing intimacy in their relationship. Jack would often include doodles and drawings. Ettie initially addressed her letters with ‘Dear Jack’ and ‘Yours, Ettie’, but abandoned that after their engagement in favour of ‘Dearest Jack’ and ‘Your Loving Ettie.’

Ettie did have other suitors – in particular a Mr Hill, who she wasn’t very impressed with, mentioning in her letters how her employer kept inviting him over. Family and friends also appeared in the letters between Jack and Ettie, with news of family and wedding arrangements.

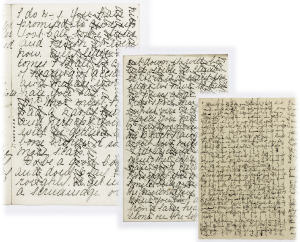

A striking feature in some of the letters is cross writing – the practice of writing a letter and turning it 90 degrees to write the opposite way. This was a common practice in Victorian letter writing to save on paper and expensive postal charges.

Jack and Ettie’s cross-writing technique may be a transcriber’s nightmare, but often they’d write several pages in this style since they were so familiar with each other’s handwriting.

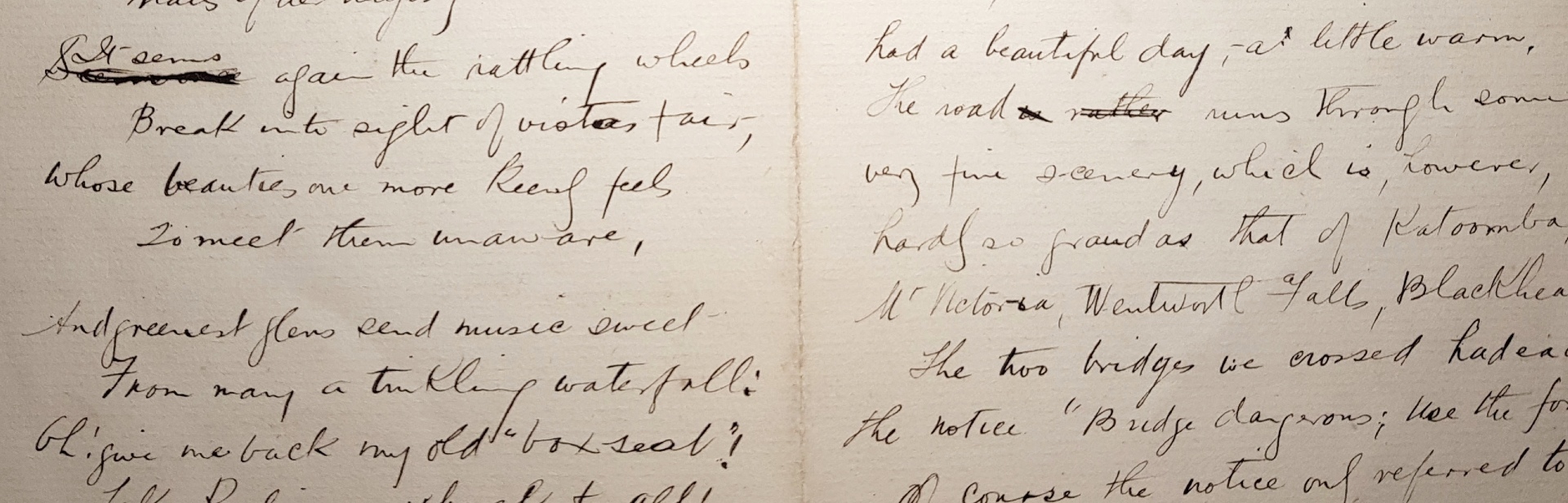

By today’s standard, Victorian love letters can read as formal documents steeped in social conventions, but there are moments in the months before their wedding when Jack stepped outside Victorian conventions and expressed himself with raw emotion. An example of Jack’s poetic fervour before their marriage:

Oh, I will kiss your eyes, & lips & cheeks & hair, until you have not breath to ask me to stop … You are my muse when I write poetry, and my angel when hints of things better & higher than those of the everyday world come in celestial colours to my mind. If I can develop at all Ettie, into a man of any consideration, it will be because you have loved & trusted me.

Historian Kate O’Neill chairs the Woodford Academy Management Committee and began researching Jack and Ettie’s letters as part of her Postgraduate degree in Local, Family, and Applied History at the University of New England. It’s thanks to her research and the support of a dedicated team of Woodford Academy volunteers, that the story behind Jack and Ettie’s letters has been revealed.

Kate says it’s rare to find a complete set of correspondence between Victorian lovers that is this candid and personal.

“These letters give the reader an insight into Jack and Ettie’s most private interchanges. At times it’s almost voyeuristic,” she says. “The beauty of these letters is their simplicity, their sweetness, and the expression of heartfelt emotions that they would not have publicly displayed. Their writings make a great love story.”

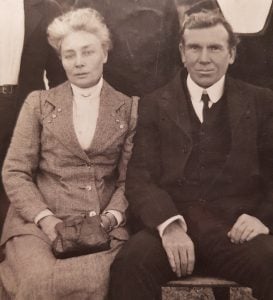

Like all great love stories, there was a happy ending for Jack and Ettie. After marrying, Jack became the first Headmaster at the newly-founded Scots College at Lady Robinsons Beach in Rockdale, Sydney. They later moved to Woollahara, Manly, and then Queensland in 1900. In 1907, Jack, Ettie and their two young daughters Jessie and Gertrude moved to Woodford House in the Blue Mountains. They renamed it Woodford Academy, and opened a boarding school for boys.

Ettie later died at the age of 42, and it’s believed that it was Jack who saved their love letters and passed them onto his daughters. Woodford Academy and its contents were later bequeathed to the National Trust in 1979, and Jack and Ettie’s love letters are now cared for by a team of dedicated volunteers and conservators.

See Ettie and Jack’s love letters at Woodford Academy, open the third Saturday of each month from 10 to 4pm. Find out more.

The National Trust would like to acknowledge Sue Henley for her work transcribing the Woodford Academy love letters, and the Copland Foundation for their funding support to digitise the letters.

As one of Australia’s longest-running conservation charities, the National Trust (NSW) cares for the art, furniture and objects in many historic houses and galleries across NSW. Help support our work and become a National Trust member.

Stay up-to-date on other historical stories

Subscribe to our free monthly e-newsletter for the latest news, events and special offers from the National Trust.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Email

Email

I have really enjoyed reading the love letters. What a loss it was to Ettie when Jack died so young.

I hope I can get up to the Woodford Academy sometime as it is ages since I have been there.

Congratulations on all you are achieving.

My history with the National Trust goes back to 1960!!