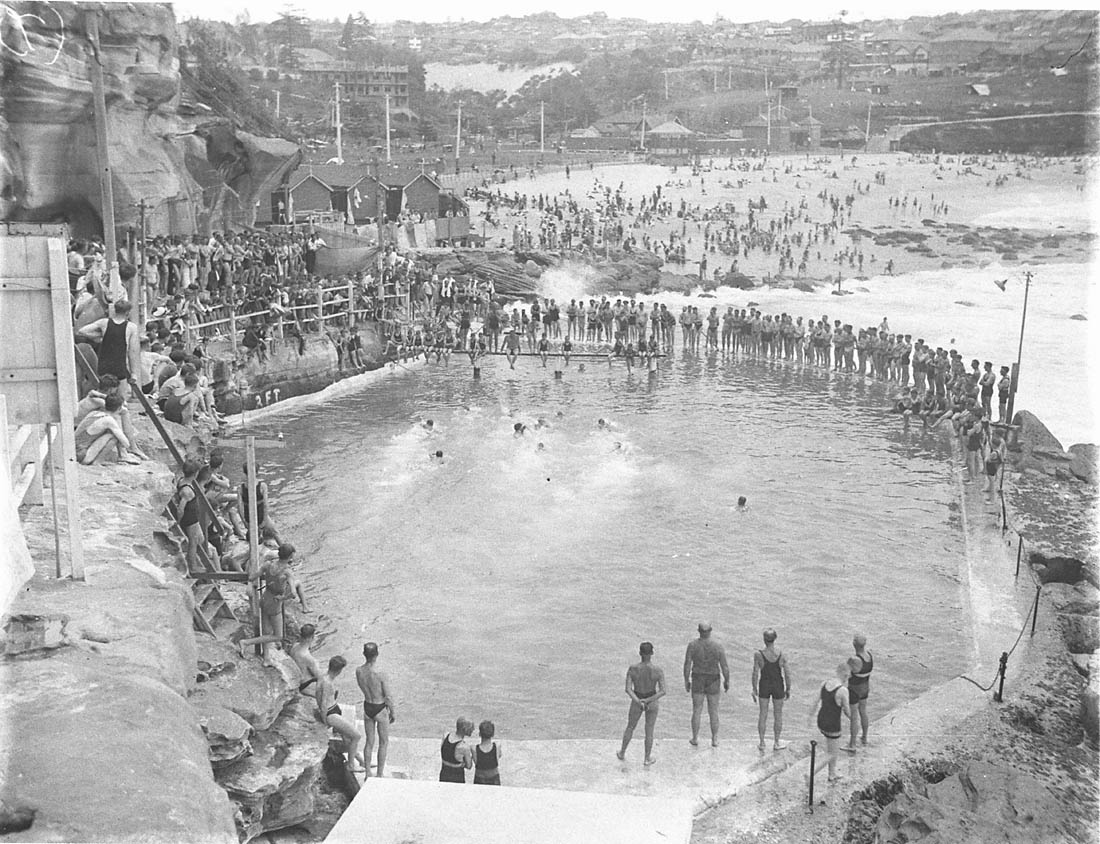

NSW’s ocean pools are an amazing asset and legacy, an iconic collection of recreational infrastructure running the entire length of our coast. But these special places are under threat. Along with the natural ravages of time and tide, ocean pools are increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Ocean pools are a deeply Australian phenomenon enjoyed by generations of swimmers, sunbakers and sightseers. NSW, in particular, has a greater concentration of ocean pools than anywhere in the world, with 60 pools between Yamba in the north and Eden in the south. In fact, if you count all saltwater swimming enclosures, such as harbour pools, netted enclosures and wharf structures, the state has about 120 ocean and harbour pools. The next closest is South Africa, with 80 saltwater enclosures nationally.

NSW’s preponderance of ocean pools reveals our deep affinity with coastal spaces and landscapes. With more than 85% of us living within 50 kilometres of the coast, it’s not hard to see why ocean pools have become such an iconic and well-loved feature. They embody many of the values we associate with the coast and the complex factors that converge there.

Ocean pools provide a tangible link between land and sea, allowing us to connect closely with the open coast. Sitting in the intertidal zone, they are exposed to currents and waves. Like natural rock pools, they fill and drain with the tides, retaining part of the sea, along with fish, crabs, jellyfish and other marine creatures. Ocean pools are designed and constructed for simplicity – just enough to create a protected space to swim. In some cases, pools are no more than one wall built along a rock platform.

A long and optimistic history

Our fascination with coastal places is not new. For millennia the coast has been a focus of habitation and activity. And while our ocean pools are, of course, post-colonial structures, some of them were certainly built on places of indigenous significance. The pool at The Entrance was listed as a state heritage item because it was known to Aboriginal people as a natural saltwater fish trap. It’s likely that other ocean pools along the NSW coast also had their beginnings as fish traps.

The main catalyst for ocean pool building was the introduction of the Municipal Baths Act of 1896, which empowered local councils to provide public baths. Many councils took this opportunity to build ocean pools to attract residents and grow their rate base. A second wave of ocean pools was built in the 1920s when the government rolled out public works projects to provide jobs and support to the community. Of all the post-war and depression-era projects, ocean pools were among the most optimistic and idealistic. The result is a legacy of unique recreational assets of great social significance and natural beauty distributed along NSW’s 2,100 kilometres of coast.

Precious but vulnerable

Today, many ocean pools are in a fragile state due to their age, construction and location, where they bear the full brunt of the elements. On top of this, climate change is making matters worse. Severe weather, including more frequent and intense east coast lows and coastal flooding, will accelerate the weakening and erosion of ocean pool structures. Poised as they are at the very edge of our shores, ocean pools are at the forefront of coastal impacts. They are, in a sense, the canary in the coal mine.

In 1994, the National Trust commissioned a survey of Sydney’s ocean and harbour pools, which led to five being recognised on the state heritage register. Others, however, remain unlisted. The National Trust report emphasised that the heritage significance of saltwater pools primarily lay in their continued function as places of recreation and exercise, rather than just their fabric. Critically, the survey also recognised the significance of pools as a group, similar to the way that lighthouses up and down the coast are recognised not only as important individual items but also part of a broader network.

We should consider NSW’s ocean pools as a true string of pearls along our coast, and as the threats continue to mount, we need to ensure these amazing public assets are conserved, protected, and in some cases revived for future generations to enjoy.

Author: Nicole Larkin is a Sydney-based architect with a deep interest in the ocean pools of NSW. She is working with the National Trust’s Landscape Committee to help protect these precious places.

This story first featured in the National Trust New South Wales magazine which gets delivered to members quarterly. Become a member today to receive many exclusive benefits.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Email

Email

I love the quote about ocean pools,”as a true string of pearls along our coast”, a fabulous description. This article was very interesting. I grew up learning to swim in the ocean pools at Newcastle and Merewether and now enjoy the ocean pools in Kiama and Gerringong. So delighted to hear of the National Trust’s work in preserving these valuable resources for all Australians.