One of Sydney’s most distinguished residential buildings, The Astor, celebrates its centenary this October. Author, publisher and former resident Dr Jan Roberts reflects on its fascinating history and some of the more famous occupants.

BY DR JAN ROBERTS, NATIONAL TRUST LIFE MEMBER

This article was originally published in the October 2023 issue of the National Trust’s member magazine.

While many of Sydney’s heritage buildings have been demolished, the Grand Old Lady of 123–125 Macquarie Street remains intact as a symbol of the optimistic, roaring 1920s.

The Astor was ‘born’ a century ago at a glittering rooftop party on 25 October 1923. It achieved some historic firsts, notably as Australia’s tallest residential building, the first of its type of concrete construction and our first experiment in co-operative housing.

It remains a Company Title apartment block, with each shareholder having equal rights, despite differences in the flats’ sizes and values. The Astor is a living exercise in democracy with all the attendant human irritations.

The building is a chameleon – all things to all people. A symbol of wealth (the name says it all); a haven for business, academic and creative women; a magnet for bohemians and eccentrics; a favourite city home for the squattocracy and Macquarie Street medicos and lawyers; and an anachronism – “yesterday’s place for yesterday’s people”. Astor habitués match the building!

The instigators were former grazier John O’Brien (1867–1948) and his wife Cicely, who grew up in Phillip Street’s Water Police Station residence with her nine siblings. The couple sold Wyoming Station in the Riverina and moved to Sydney for a dramatic change of lifestyle. Influenced by new American ideas expressed in architecture and religion, they became enthusiastic believers in Christian Science.

In ‘CS’ circles they met the architects Donald Esplin and Stuart Mill Mould, who were among the first shareholders in The Astor. Letters reveal the client-architect relationship was often turbulent.

Building 52 flats with a basement and rooftop, and dealing with demanding shareholders and prospective buyers and tenants, proved challenging. The O’Briens’ marriage broke up and they lived separately, not speaking, in The Astor for many years.

Like many of The Astor’s residents, the O’Briens were wealthy, older and childless. They chose to live in a home in the city instead of suburbia or the bush. The building had a restaurant, which provided a silent butler service to their kitchen. Staff and a live-in caretaker relieved them of domestic chores.

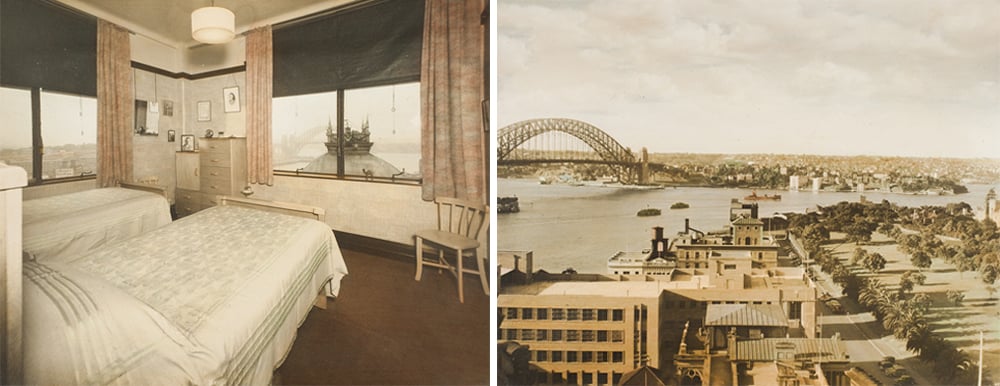

Although The Astor has no parking, cars could be garaged nearby. The incomparable position of the building with stunning views of Sydney Harbour and the Royal Botanic Garden compensated for board meeting dissent and personal squabbles!

The National Trust and The Astor began their long association because of S.H. ‘Harry’ Ervin (1881–1977), who owned Flat 2 on the 11th floor from 1926 until his death there in 1977.

When Ervin’s sister married the successful wool broker Karl Lothringer, he took young Harry into his business. Years later their son Hans, a chartered accountant, helped Harry set up mechanisms to make bequests to the National Trust, which led to the establishment of the S.H. Ervin Gallery.

Harry Ervin was not always in residence at The Astor. While the Sydney Harbour Bridge was being built, he leased his flat to Lawrence Ennis, who managed the project for Dorman Long & Co.

The Scottish engineer was able to watch progress every day through a long telescope. The ‘who’s who’ roll call of other Astor residents is a long one. The serious, the fun-loving, the scandalous, their names are written into history of one kind or another.

Portia Geach, Ruby Rich, Barry Humphries, Jean Garling, Sir Roy and Lady McCaughey, Major Rubin, Sir Hugh and Lady Denison, Adele Weiss, Sir Tristan and Lady Antico, and Cate Blanchett. Even Captain De Groot, the infamous antique dealer who rode his horse through the assemblage to cut the harbour bridge ribbon before Premier Jack Lang, plays a part in the story.

The Astor was heritage listed by the National Trust in 1980. Her graceful survival was further assured by the adroit surgery of two exceptional chairs of The Astor board. Its first female leader, Ann Ryan, excised concrete cancer in the mid-1990s.

More recently Trevor Scott solved long-term problems associated with the large windows. We salute them as we stroll down Macquarie Street and watch The Astor glide into her second century.

Discover more

Want to find out more about remarkable heritage places across NSW? Sign up to our free newsletter for the latest news and events from the National Trust (NSW).

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Email

Email