Tucked away in Sydney’s inner west, Haberfield stands out for its character homes, wide streets and private gardens.

In anticipation of our upcoming tour of Haberfield on the 30 April with local historian and former president of the Haberfield Association, Vincent Crow, we take a look at what makes this Federation-era suburb so special.

By Michelle Bateman, Editor of National Trust (NSW) magazine

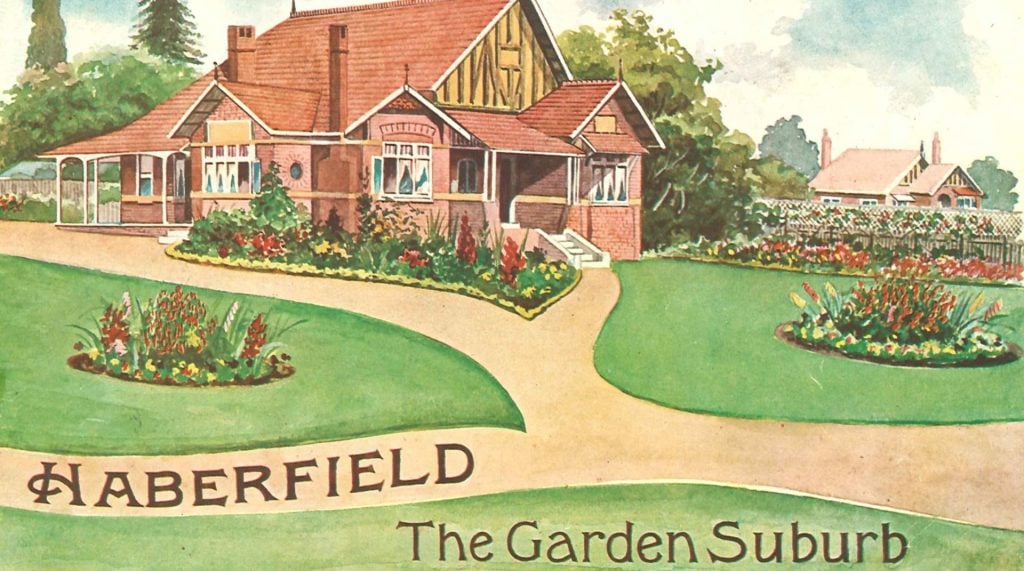

A garden estate

1901, Haberfield Estate was marketed as Australia’s earliest ‘garden suburb’ but it quickly gained another nickname, dubbed by cheeky newspaper journalists as the suburb that was ‘publess, slumless and laneless’. “There was no hotel in Haberfield, though there was a small wine bar with saloon-style swinging doors,” explains local historian and former president of the Haberfield Association, Vincent Crow. “And it was laneless because, from the beginning, all houses were connected to the Bondi sewage scheme, removing the need for night carts.”

This gentrified estate was the crowning achievement of forward-thinking real estate agent and property developer Richard Stanton, who purchased and subdivided the land with a clear idea of the amenities he wanted to provide middle-class families tired of squeezing into inner-city terrace housing. “Every house had its own garden and every house was single-storey and separate, not attached,” adds Crow. “Each house had a street tree in front of it, mostly brush boxes, a native from Queensland.”

Haberfield’s development took place over a period of almost 25 years and the houses reflect the changing tastes of the times, as late-Victorian-era architecture made way for Federation houses, followed by the Californian-style bungalows of the 1920s. Its architectural significance led to Haberfield being classified as a conservation area by the National Trust in 1979 and many of the homes remain beautifully preserved today. As Haberfield prepares to celebrate its 125th anniversary in 2026, we take a look at some of the more surprising facts about this inner-west locale.

It was an early blueprint for today’s suburbs

Subdivisions and housing estates are commonplace today but in the early 20th century, the concept was revolutionary. Developer Richard Stanton was inspired by the burgeoning English concept of a garden city that was touted as a panacea to London’s Industrial Revolution-fuelled building boom. He conceived of a ‘garden suburb’, where prospective property purchasers could visit an on-site showroom to select a plot of land and work with the estate’s architect to plan the look of their home. “Out the back was a huge room full of mantlepieces, fireplaces and bathroom fittings, and you could choose all the fixtures for your home,” adds Crow. Stanton’s model took off, and became a reference point for future residential development across the country.

No two houses are identical

The Haberfield Estate had its own its own in-house architect – originally Daniel Wormald (from 1903 – 1904), followed by John Spencer-Stansfield (1905 – 1914) – who ensured the homes adhered to a particular aesthetic as the suburb grew. But while they followed a similar template, no two houses are identical, which Crow says was a selling point at the time. “In the original sales brochure they printed ‘no two properties of the one design’ in big capital letters. Each street had side fences of the same design to give visual cohesion to that street, while offering variety across the suburb.”

There are clues in the small details

To the well-practiced eye, the smallest features of a home can often reveal big differences about their architectural provenance. Take the design of the leadlights: “The earlier homes often hark back to the Victorian style, with round or geometric designs,” Crow explains. “This is quite different to the Federation homes, where the Art Nouveau influence started to creep in, with its more ornate designs. In one example, the leadlight’s design flowed from the sidelight to the fanlight over the front door, thereby enveloping the front door.” The front hallway of a house offers another clue: “Until about 1910, the houses often had Victorian pilasters on the side of the hallway, where later houses are designed with a timber screen in the hallways.”

High fences were banned

Large shrubs and high fences were prohibited in the front yard to encourage neighbourly interaction. Instead, Wormald and Spencer-Stansfield maintained privacy by positioning each home further back on its block, with a serpentine pathway and well-maintained garden leading from the gate to the front porch. “The idea of the garden suburb was to place the house ‘inside’ a garden,” says Crow. “This links each private garden with the public streetscape, and its trees and nature strip.” And of course, it made it all the easier for passersby to admire the architecturally-designed homes of the Haberfield Estate.

Take a peek inside these homes

Join a tour of Haberfield led by local historian Vincent Crow on 30 April to visit three stunning homes representing the suburb’s primary architectural styles, as they transitioned from Federation to Californian bungalow. Here’s a small taste of what you’ll see…

WERN

The earliest house on the tour, Wern dates to 1903 and was likely designed by original Haberfield Estate architect Daniel Wormald. Its early Federation style references Victorian design influences, including the acorn-top picket fences. “These were sometimes used in Haberfield as late as 1910,” Crow notes.

WOODROW VALE

Built in 1906, this mid-Federation-period home was designed by John Spencer-Stansfield, the long-standing architect responsible for much of Haberfield’s distinct aesthetic.

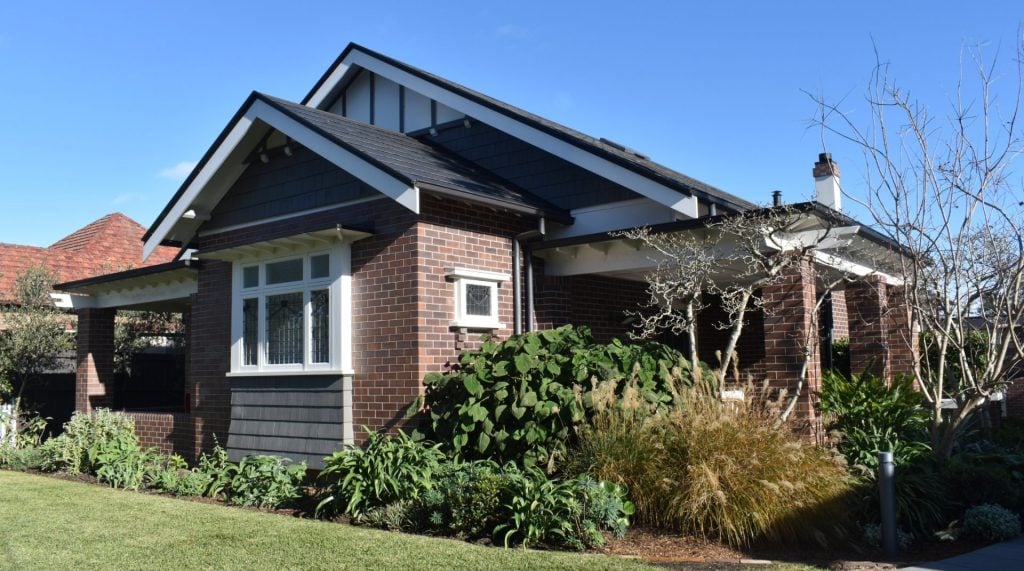

CALIFORNIAN BUNGALOW

First occupied in 1922, this Californian bungalow is located in what was originally known as the Dobroyd Point Estate, developed by the Haymarket Permanent Land, Building and Investment Company. “This property is on a larger-than-usual block of land in Haberfield and shows the continuing influence of Richard Stanton’s garden suburb concept,” Crow explains.

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Email

Email